The Tolling Bell Of Revolution – Why The World Needs Allamah Muhammad Iqbal Now More Than Ever

When I first told my Tunisian teacher that I was writing my dissertation on the thought of the late 19th/early 20th century philosopher-poet of the Indian subcontinent, ʿAllāmah Muhammad Iqbal, he immediately recited one of Iqbāl’s most famous lines that had been translated into Arabic:

China and Arabia are ours, India is ours

We are Muslim – the entire world is our homeland

I wasn’t surprised that my teacher had memorized lines of Iqbāl’s poetry, nor that he was even familiar with his thought. There was once a time, not too long ago, when Iqbāl had animated movements across the Muslim world; when his poetry was translated to several Muslim languages; when philosophers and statesmen crowned themselves champions of Iqbālian thought.

Then, like a forest fire put out by a sudden deluge, Iqbāl disappeared from the collective Muslim imagination. He disappeared because Iqbāl is hope incarnate, and we are a people in despair. He disappeared because he is life incarnate, and we are a people whose lives are akin to living death. As Ghalib, the court poet of the last Mughal emperor said a generation before Iqbāl:

They say people live on hope

We don’t even have hope to live

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we’re at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small.

Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you’re supporting without thinking about it.

The cause of our sorrow, our despair, our living death, is that we are a people twice defeated. Our first defeat began with the incursions into, then conquests, then complete subjugations by European powers of Muslim lands. We were overwhelmed, enslaved, pillaged. Violence of all kinds was meted out without mercy or recourse: physical, social, economic, epistemic, and spiritual. But the Muslim body can be chained; the Muslim society can be ravaged; the Muslim economy can be pillaged; the Muslim episteme can be tarnished; but the Muslim spirit cannot be so easily broken:

We are not ones who can be subjugated by falsehood

O sky! You have tried us a hundred times before

– Iqbal, “Tarāna-e-Millī”

Two hundred years of colonial rule led to the independence movements of the 20th century, and, after World War 2, Muslims successively cast off the yoke that had so long suffocated us. Those were decades of hope, when movement turned to triumph, and triumph turned to jubilation. And yet, that jubilation was not to last. Our yoke had not been cast off; rather, it was simply transferred from one hand to another. We had not escaped the colonial system; it had simply changed forms. Jubilation turned to realization, realization turned to desperation, and desperation finally settled into an unending melancholy, an endless depression. Twice conquered; twice defeated.

But Iqbāl was, as is so often the case, entirely correct. This ummah can be defeated; it can be subjugated; but it cannot be so easily broken. We are witnessing a complete revival of radical anti-colonialism amongst our youth. Whether their imaginations were sparked by the protests of the Arab spring; or they were inspired by the solidarity of Black Lives Matter; or their belief in resistance erupted with the global outrage over the genocide Israel has perpetrated on the Palestinian people in general and the people of Gaza in particular; the youth have traded the lethargic depression of their parents for active resistance.

Unlike their previous generations, however, they are divorced from the past projects of Islamization of knowledge or Islamic political dreams. Mawdūdi and al-Banna are distant names to them, if they’ve even heard of them. The education in resistance came from Fanon and Said, not Iqbāl and Shariāti; and older generations of Muslims who are disillusioned by their own projects of resistance offer them nothing but snide remarks and a politics of eschatological quietism – an alternative that the young and hopeful rightfully and profoundly reject.

And that is why, in this moment of a second uprising a hundred years after the first one, we need the foremost thinker of Islamic revolution, Allāmah Muhammad Iqbal, once more. We are again at a crossroads in history. If we are not able to offer an authentic, Islamically founded, and Islamically grounded theory of practical resistance, our youth will gravitate further towards ideologies that have profoundly extra-Islamic foundations; and, in the process, they will fight for the liberation of Muslims in exchange for their own Islam.

If, however, we can reach into the depths of our intellectual heritage and forge a reinvigorated Islamic decoloniality rooted in the love of Allah  and His Messenger

and His Messenger  , we can capture the energy of an excited ethic of resistance, breathe new life into a defeated ummah, and resurface an Atlantis-like drowned Islamic civilization from the seas of darkness.

, we can capture the energy of an excited ethic of resistance, breathe new life into a defeated ummah, and resurface an Atlantis-like drowned Islamic civilization from the seas of darkness.

Iqbal: The Man and the Thought

Iqbāl as a man was the perfect image of his thought: the son of Kashmiri migrants to Sialkot, Punjab, who was educated in India, England, and Germany but wrote in Farsi and Urdu (languages that were, at the time, natively spoken by almost no one in his chosen city of residence, Lahore), Iqbal lived between cultures, between centuries, between traditions, between languages, and somewhere between the freedom he desperately dreamed of and the subjugation he was born into. His father was an illiterate store owner, and Iqbāl was the first in his family to be completely educated – only to become one of the foremost Muslim intellectuals of the last 200 years. When asked why he didn’t write an autobiography, Iqbāl responded that his thought was far more interesting than his life. In general, I agree, and so I will spend little time on his life and much more on a basic sketch of his thought.

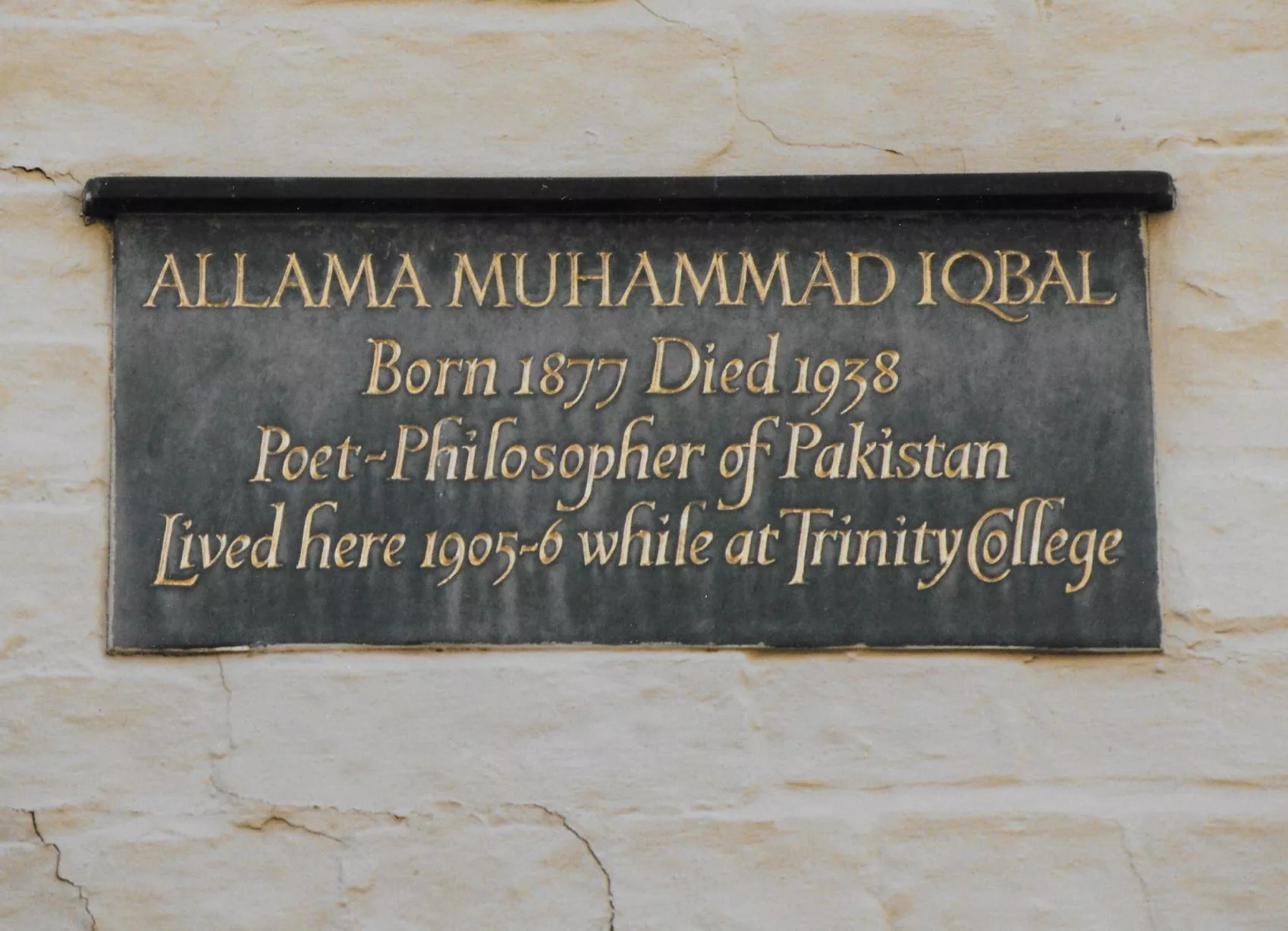

Plaque at Portugal Place, Cambridge signifying that Allama Iqbal lived there whilst he was a student at Trinity College, Cambridge [PC: Wikipedia]

Iqbāl was educated in both India and Europe (England and Germany) in some of the finest colleges of his time, including Cambridge. He spoke Punjabi, English, Urdu, Farsi, and German (which he learned in a few months) and wrote poetry in each of those languages except English. He mastered the Western and Islamic philosophical canons, Islamic metaphysics (both mystical and theological) as well as the poetic canons of Farsi and Urdu. His own thought was almost impossible to trace back to any major thinker: he was as influenced by Ibn Sīna and Rūmi as he was by Nietzsche and Bergson. Iqbāl was a master of synthesis and an heir to traditions both East and West, bringing together ancient and modern metaphysics with new disciplines like economics and sociology. He was, in almost every way, a school in and of himself in that he was indebted to every tradition that he was exposed to and mastered but belonged to none of them entirely.

The Basics of Iqbālian Thought

His thought, as well, is difficult to trace back to any one figure. The basic question that animated Iqbāl’s inquiry was that of colonialism – specifically, why the Muslim world had become so utterly subjected to colonial empires. Unlike his contemporaries, however, Iqbāl did not resort to easy answers. Instead, he understood the foundations of the colonial system and set his sights on understanding the ways in which it is perpetuated. His inquiry brought him face-to-face with a stark and desperate realization: that Muslims are willing participants in their own subjugation, and that colonial rule would be impossible without the willingness of Muslims to sell the struggle of freedom in exchange for a more comfortable slavery. This led to a final question, one that would absorb him for the entirety of his life: why are Muslims so comfortable being slaves when Allah  has called them to embrace their role as the best of nations brought about for mankind?

has called them to embrace their role as the best of nations brought about for mankind?

Iqbāl’s answer was that colonial subjugation affects the Muslim at such a deeply emotional level that it profoundly alters the very way Muslims imagine themselves. The shock of such overwhelming defeat and the methods of control inherent in colonial orders broke the Muslim self-imagination, and the ummah had fallen into intense depression and despair. This psychological state had metaphysical implications. A desperate, depressed person has no hope in Allah  , and despairing in the Mercy of Allah

, and despairing in the Mercy of Allah  is tantamount to disbelief. And so, when this hopeless Muslim was asked to exchange his love for Allah

is tantamount to disbelief. And so, when this hopeless Muslim was asked to exchange his love for Allah  and His Messenger

and His Messenger  for a more comfortable slavery, hopelessness allowed him to acquiesce.

for a more comfortable slavery, hopelessness allowed him to acquiesce.

Colonial rule led to a fundamental reimagination of what it means to be Muslim, and that broken spirit eventually led to an individual and communal loss of love for Allah  .

.

Khudi

It was from this point of departure that Iqbāl crafted his most important philosophical concept that animated his entire work – the concept of khudi (selfhood). In classical Sufi thought, where the chief good was dissolving the self in the love of Allah  , khudi was the chief antagonist. For Iqbal, however, khudi was both the beginning of the spiritual path and its end.

, khudi was the chief antagonist. For Iqbal, however, khudi was both the beginning of the spiritual path and its end.

At the beginning of the path, the heedless, unreformed person is self-important, selfish, and driven by his base desires (a state the Sufis of old called khudi in Farsi and Ananiyyah in Arabic). He is unrefined in character and capable only of looking out for himself and his whims. Then, the person begins to grow his love for Allah  and His Messenger

and His Messenger  until it reaches such a point that everything loved by Allah

until it reaches such a point that everything loved by Allah  is loved by him and everything hated by Allah

is loved by him and everything hated by Allah  is hated by him. His love for the divine consumes him like the love of a lover for his beloved.

is hated by him. His love for the divine consumes him like the love of a lover for his beloved.

When a person reaches this state, he recognizes the heavy burden and incomparable honor that Allah  has given His truest servants: that of khilāfah (vicegerency) on this earth. The Muslim is not only the worshiper and lover of Allah

has given His truest servants: that of khilāfah (vicegerency) on this earth. The Muslim is not only the worshiper and lover of Allah  ; he is also His representative on earth. When he recognizes that, a Muslim reaches the true beginning of the spiritual path – one that takes him right back to his khudi. This time, however, this khudi is neither self-obsessed nor selfish. Instead, selfishness is replaced with a deep sense of sovereignty of self.

; he is also His representative on earth. When he recognizes that, a Muslim reaches the true beginning of the spiritual path – one that takes him right back to his khudi. This time, however, this khudi is neither self-obsessed nor selfish. Instead, selfishness is replaced with a deep sense of sovereignty of self.

This is manifested not only in complete obedience to Allah  and His Messenger

and His Messenger  but also in a complete refusal to bow one’s head to subjugation. A Muslim is too self-sovereign to be a slave. He is too proud of his role in the world as a representative of Allah

but also in a complete refusal to bow one’s head to subjugation. A Muslim is too self-sovereign to be a slave. He is too proud of his role in the world as a representative of Allah  to sell himself for comfortable slavery. A Muslim is meant for the vicegerency of Allah

to sell himself for comfortable slavery. A Muslim is meant for the vicegerency of Allah  on this earth, and that can only be achieved when he is entirely free.

on this earth, and that can only be achieved when he is entirely free.

Why We Need Iqbāl Today

In many ways, Iqbāl’s thought was much ahead of his time. He may have written his most important works in the 1930s, but they wouldn’t be entirely understood till 2030. Core to his understanding of colonialism is that colonial regimes are sustained by an international socio-economic order, and that force of arms is secondary to force of thought and force of wealth. The Muslim elite is purposefully brainwashed by a Western education system that embeds everything good and moral and reasonable within Western thought and divorces the Muslim from his own intellectual heritage and legacy. The Muslim is educated in Western thought and illiterate in his own. Then, this spiritually unrefined and illiterate person is offered lucrative careers and contracts in systems that perpetuate the subjugation of his own people.

For Iqbal, if Muslims refused to participate in the intellectual and economic foundations that underpin the colonial order, colonialism would eventually collapse. In order to do so, however, a true Muslim civilizational revolution would have to create its own economic, political, and cultural order – one that had the technological and industrial know-how, personal ingenuity, and communal commitment to goodness and justice to sustain itself. It would also need the depth of understanding of its own intellectual and spiritual heritage and marry it with brilliance in analysis and critique of European modernity to avoid benign a crude, off-brand knock-off for Western civilization – to be a real alternate Muslim modernity and not a European one with a sticker of a Quran slapped on top of it.

As I’ve written before, Muslims have been fooled by the international liberal order for more than half a century. Muslim movements believed that force – not culture and economics – was the primary means of maintaining the colonial order in the world. We have come to realize – perhaps most powerfully demonstrated by the genocide in Gaza – exactly what Iqbāl had almost a hundred years ago: that the boots on the ground are secondary and purchasing Muslim acquiescence to subjugation is the primary mode of colonialism.

This is a moment of history, one in which Muslims will either lose themselves forever or realize that freedom is our birthright, the prerequisite to fulfilling our spiritual purpose as khulafāʾ (vicegerents) of Allah  on this earth. We are not like other nations. We are the heirs of prophets, the carriers of tawḥīd, the representatives of Allah

on this earth. We are not like other nations. We are the heirs of prophets, the carriers of tawḥīd, the representatives of Allah  on this earth. And the moment of our uprising is upon us – if only we recognize and accept who we are.

on this earth. And the moment of our uprising is upon us – if only we recognize and accept who we are.

This ummah will not be liberated as a hobby to take a break from our 9 – 5 jobs and to enrich our American dreams. It is a social, cultural, economic, political, intellectual, and spiritual project. Our task is the reconstruction of an entire civilization, not remodeling a deck. It all begins with remembering and believing in who we truly are – and the one who reminds us most of who we are is ʿAllamah Muhammad Iqbāl.

We Are Unicorns in a Herd of Horses

What’s the difference between a unicorn and a horse wearing a party hat? There are two: reality and belief. Imagine a unicorn that grew up in a herd of horses that wear party hats on their head. To an onlooker, there is no difference between the unicorn and the horses: they all look like horses, and they all have a cone on their head. The unicorn itself might even be excused in thinking that it is, in fact, just another horse – that its horn is nothing more than a decoration.

What separates that unicorn from all the other horses is its unicorn-ness – that its essence is different, its capabilities are different, its responsibilities are different. But that inherent difference does not mean that the unicorn will necessarily practice and achieve the potential of its unicorn-ness. First, it must believe that it is, in fact, a unicorn. Every moment that the unicorn spends doubting itself is a moment that it fails to live up to its potential. Every moment that a unicorn behaves like just another horse is another day the unicorn has wasted its life.

We are the ummah of Muhammad  , the heirs of prophets, the protectors of the banner of tawḥīd. We are the unicorn in a herd of horses:

, the heirs of prophets, the protectors of the banner of tawḥīd. We are the unicorn in a herd of horses:

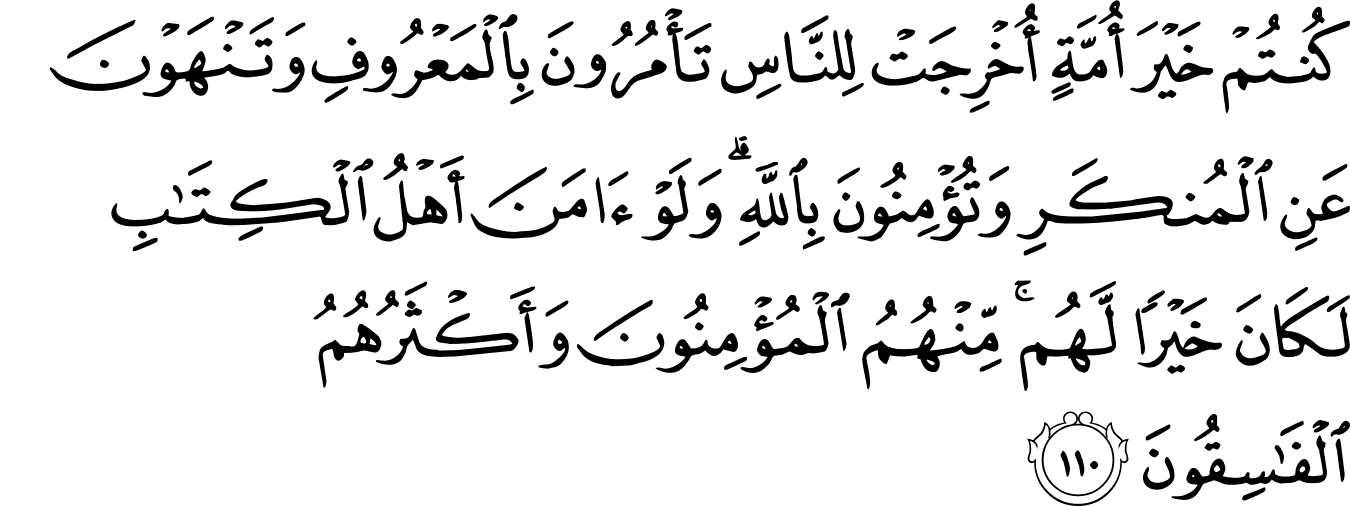

“You are the best nation produced [as an example] for mankind. You enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong and believe in Allah. If only the People of the Scripture had believed, it would have been better for them. Among them are believers, but most of them are defiantly disobedient.” [Surah ‘Ali ‘Imran: 3;110]

We have lived surrounded by horses wearing party hats, been ridiculed for our horn, until we ourselves have begun to believe that we are just another horse wearing another party hat. We have become embodiments, manifestations of the powerful couplet by al-Mutanabbi:

I have not seen anything from the faults of men

Like the capable failing to reach their potential

We are not like the strong failing to be strong, or the intelligent failing to be intelligent, or the humorous failing to be amusing; we are the best nation brought about for people failing in our God-given responsibility to act as His vicegerents on this endarkened world. We fail to be the unicorns we are, not just because we have stopped acting like them – but because we have even lost our belief in them.

We have to choose to bet on ourselves – to not simply run the race made for everyone else, but to create the race that we were always made for. As Iqbāl says in one of his most famous poems, Jawāb-i-Shikwa:

The mind’s your armor, and love’s your blade!

My dervish! Your reign holds the world in gaze!

Your call sets all but Allah ablaze!

Be Muslim, and fate is what you have made!

Be true to Muḥammad, and We are yours;

Not just this world: the pen and slate are yours!

[This article was first published here]

Related:

– Seeking Out The Spiritual Underpinnings Of Our Ritual Acts of Worship