Rising To The Moment: What Muslim American Activists Of Today Can Learn From Successful Community Movements During The Bosnian Genocide

In these times of rampant injustice and oppression in Palestine, one figure seems to be constantly on the minds of the Muslim American: Musa  . From khutbahs to lectures and one on one conversations, since Israel’s genocide in Gaza began we have turned to remembering Musa

. From khutbahs to lectures and one on one conversations, since Israel’s genocide in Gaza began we have turned to remembering Musa  as an exemplar of standing up to tyranny for the sake of Allah

as an exemplar of standing up to tyranny for the sake of Allah  . His steadfastness, trust in Allah

. His steadfastness, trust in Allah  , and commitment to justice are all traits we are striving to learn from.

, and commitment to justice are all traits we are striving to learn from.

There is, though, one other part of Musa’s  story that has perhaps gone underexplored but one that is intensely relevant to our time: his willingness to step up at a moment’s notice. Reading Musa’s

story that has perhaps gone underexplored but one that is intensely relevant to our time: his willingness to step up at a moment’s notice. Reading Musa’s  narrative and knowing how it ends, it can be easy for us to forget just how shocking receiving Allah’s

narrative and knowing how it ends, it can be easy for us to forget just how shocking receiving Allah’s  Call may have been for him. At the time of his call to prophethood, Musa

Call may have been for him. At the time of his call to prophethood, Musa  had an established life; a settled, comfortable life in Midian complete with a job and family. Being told to return to Egypt, a place of oppression and terrible memories, and to not only return but to put his life at risk by confronting the tyrant who he had fled in the first place, was likely quite the shock; a complete and sudden rupture of his status quo. And yet, Musa

had an established life; a settled, comfortable life in Midian complete with a job and family. Being told to return to Egypt, a place of oppression and terrible memories, and to not only return but to put his life at risk by confronting the tyrant who he had fled in the first place, was likely quite the shock; a complete and sudden rupture of his status quo. And yet, Musa  stepped up. He rose to the occasion despite not even knowing exactly what his mission would entail, let alone what the consequences might be.

stepped up. He rose to the occasion despite not even knowing exactly what his mission would entail, let alone what the consequences might be.

This element of Musa’s  story stands out today, as many of us find ourselves asking whether we will risk comfort to step up; to answer our calling as Muslims to stand up for justice in ways we cannot anticipate or predict. Many Muslims have found themselves suddenly called upon to take roles they would not have imagined themselves in previously: masjid communities have answered urgent calls for donations and support from college encampments, Muslim students have found themselves leading chants, giving interviews, and planning a movement, and we all feel compelled to bear witness and speak up about the atrocities happening in Gaza. Like Musa

story stands out today, as many of us find ourselves asking whether we will risk comfort to step up; to answer our calling as Muslims to stand up for justice in ways we cannot anticipate or predict. Many Muslims have found themselves suddenly called upon to take roles they would not have imagined themselves in previously: masjid communities have answered urgent calls for donations and support from college encampments, Muslim students have found themselves leading chants, giving interviews, and planning a movement, and we all feel compelled to bear witness and speak up about the atrocities happening in Gaza. Like Musa  , we have found ourselves stepping into the role of advocate in unexpected ways.

, we have found ourselves stepping into the role of advocate in unexpected ways.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we’re at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small.

Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you’re supporting without thinking about it.

This feeling is not without precedent though. In the spirit of practicing the Prophet’s  injunctions that “the believers are like one body in compassion” and “the believers are like bricks of a building, each part strengthening the other,” we must remember that we can draw on the struggles for justice of past Muslims for inspiration. We are not the first to be called to oppose tyranny and we ought to remember the Muslims who came before us, appreciating the long tradition of the ummah standing up in unprecedented ways.

injunctions that “the believers are like one body in compassion” and “the believers are like bricks of a building, each part strengthening the other,” we must remember that we can draw on the struggles for justice of past Muslims for inspiration. We are not the first to be called to oppose tyranny and we ought to remember the Muslims who came before us, appreciating the long tradition of the ummah standing up in unprecedented ways.

One important moment in this tradition was Muslim American involvement in the campaign to end the genocide in Bosnia in the 1990s, a moment where Muslim-Americans found themselves called upon to step up and organize in unanticipated ways. There is much more to say about this period than this article can capture, so the following sections are intended as just a brief introduction to some of the key histories we should remember today. Based on interviews with participants and written materials they have previously published, this is an invitation to reflect on what earlier moments of standing for justice and against genocide can teach us today.

Creating the Bosnia Task Force

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, Serbian nationalists aiming to construct a “Greater Serbia” began a campaign of ethnic cleansing and genocide towards Bosniaks (the term for ethnic Bosnian Muslims). Faced with news and photos of massacres, concentration camps, and mass rapes, American Muslim leaders and communities knew they had to take some stand for justice on behalf of their fellow Muslims. However, there was no developed infrastructure for such large-scale Muslim organizing in the United States: the community found itself having to learn to unite and organize on the fly in response to a clear calling to witness the atrocities being committed.

In the summer of 1992, this sense of needing to act produced the Bosnia Task Force, a coalition of different mosques from across Chicago and national Muslim organizations like the community of W. D. Mohammed and ISNA. BTF was incredibly improvised, produced by the community sensing the need to step up but without having prior experience with creating a national political campaign. As Imam Mujahid, the eventual national director of the BTF, described it in an interview, he was persuaded to step into the role despite initial reluctance: having “never hired anybody,” he was suddenly tasked with hiring a staff and developing an organization using an initial budget of fifty thousand dollars provided by Chicago masajid. From a basement office in Chicago, with one-full time and two-part time staff members, a fax, two phones, and student volunteers sitting around a table, organized Muslim-American efforts to speak up began.

Empowering a Community

Vitally, though, organizing was not focused only on the Bosnia Task Force: BTF’s work would have been impossible without a grassroot network of masjids and their communities across the nation who made the strategic vision developed in Chicago into a reality. As Imam Mujahid puts it in his writings on the experience, “It would be wrong to claim much credit for Bosnia Task Force, USA since the work to stop genocide in Bosnia became a true grassroots movement in the Muslim community.” Essentially, organizing worked through BTF sending out action alerts via fax and phone to local communities who would then organize within their masajid to put the national strategy into action. As Imam Saffet Catovic, who at the time worked to coordinate the outreach and organizing efforts in the United States for the Bosnian Mission to the UN, put it in an interview, the campaign was not just the national leadership in Chicago: it was the product of many smaller campaigns and organizing efforts across the country, the result of everyday Muslims devoting themselves to the cause of the ummah. Or, as Imam Mujahid eloquently writes, “Many people sacrificed their time and jobs to work tirelessly to stop genocide in Bosnia,” the product of “a sudden wake-up call after seeing the horrors” and thinking “Should we not stand up against injustice for once instead of clucking our tongues in sympathy and then forgetting about the issue?”

It’s impossible to understate how significant a development this rising to the occasion by Muslims across the country was. Describing the landscape of the Muslim-American community in the face of the genocide, Imam Saffet notes that, beyond simply having never done it before, there were considerable psychological and structural barriers to organizing in place that Muslim-Americans had to overcome. Islamophobia, on the rise in the wake of Western panic in response to the Iranian Revolution, presented a formidable threat. As a largely immigrant community, many Muslims were already in precarious positions, leading to a communal attitude of keeping your head down and avoiding political risk; this attitude was only reinforced by the fact that many carried with them the experience of immigrating from countries where repressive governments made any public activity dangerous. With these historic constraints, Muslim-Americans simply did not have much of the experience that helps make a successful campaign; as Imam Saffet put it, it’s difficult to hold a protest when you have never filed for a permit, meet with a member of Congress when they’ve never heard of you, or receive national media coverage with no press connections.

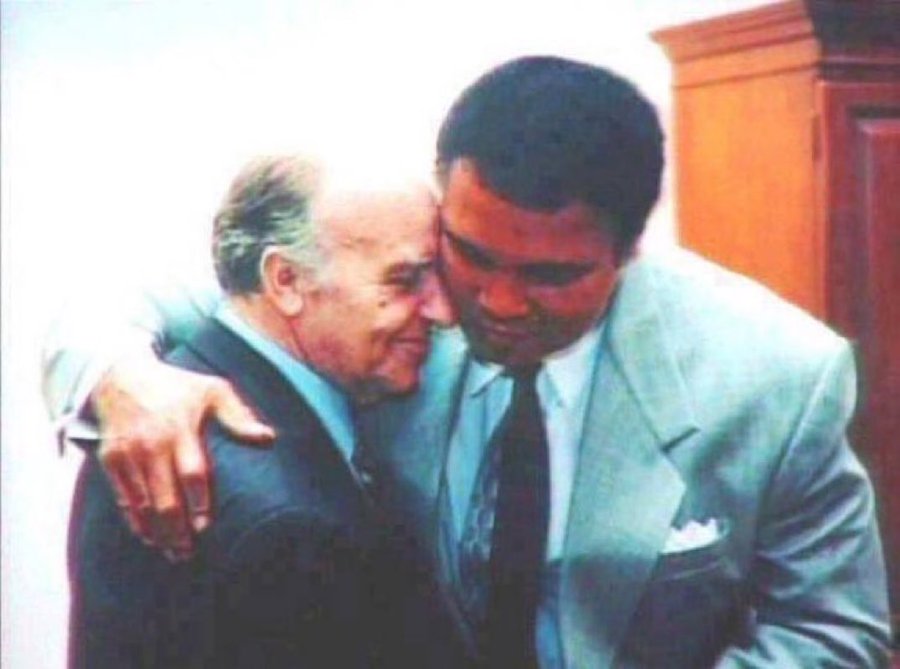

Muhammad Ali meeting with Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović

But these barriers were, in fact, overcome: Muslims came out to the streets for actions held across the country in massive numbers. This included traveling from all over the country to attend a national rally in Washington, DC, which was endorsed by Muhammad Ali and attracted a crowd estimated to be anywhere from a hundred thousand to a quarter million, drawing, most likely for the first time, national media coverage by outlets like CNN and the Washington Post to an effort undertaken by the Muslim-American community. Imam Saffet and Imam Mujahid both stress just how significant this DC rally was: a community largely isolated from the American political scene suddenly stepped decisively onto the stage, many traveling long distances when they had never even previously attended a protest. Rather than be deterred from striving for justice, Muslim-Americans claimed a powerful sense of agency, highlighting the power of the community when it feels nothing, no worldly obstacle or consideration, is more important than rising to the moment of need.

Changing International Law

The power of this grassroots activism would quickly be proven. Muslim Americans changed the conversation on not just a national level, but an international one in ways that would have significance even after the 1995 Dayton Accords formally ended the conflict in Bosnia. While based in the United States, organizing around Bosnia reflected a truly international vision; a vision of solidarity within the ummah that goes beyond national borders. Pressure was put on American politicians, but the aim, ultimately, was to impact global politics. An example of this was Muslim American organizing to lift the UN arms embargo which prevented Bosnians from getting the tools they needed for self-defense—by pressuring the White House and members of Congress, Muslims were successful in getting Congress to pass a resolution calling for the lifting of the arms embargo, reflecting a successful strategy of starting from local politics to influence the global.

One particularly important example of this strategy is the decisive role of Muslim-Americans in having rape declared a war crime. As famed scholars of law and gender like Catherine MacKinnon have noted, the response to the Bosnian genocide was key to making people and legal institutions aware of the need to protect the human rights of women and prosecute the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war. The idea that international human rights law could address sexual violence and rape could be charged as a war crime came to prominence through Bosnia, and, as Imam Mujahid recounts, the idea for the strategy came from a group of college students, sitting around a table in a basement office in Chicago. From that table, the strategy grew to an unlikely and unprecedented alliance between Muslim-American organizers and prominent feminist organizations like the National Organization for Women that led to rallies in cities across the country, eventually leading to tangible declarations in international law that rape was a war crime. These grand changes in international law were produced by the grassroots efforts of Muslim activists like Aminah Assilimi who should be household names and who reflected a vision of unity across the ummah that goes beyond the artificial boundaries of the nation-state.

Forging Alliances

As the successful effort to have rape declared a war crime shows, the response to the Bosnian genocide was also an important moment for the Muslim community coming out of its shell and learning to manage alliances with diverse groups. Resonating with the experience of Muslim-Americans working in the diverse pro-Palestine encampments across the country, in the case of Bosnia the community had to quickly figure out who to align with and how. In the case of working with organizations like NOW, for example, Imam Mujahid describes how sisters involved in the movement had to navigate explaining hijab in terms of personal choice that were understandable to left-leaning feminists. Similarly, Imam Saffet notes that Muslim communities had to suddenly and quickly learn how to do interfaith organizing. Many mosques, he notes, had few connections to the communities around them until, when news reports of a genocide against Muslims spread, groups from nearby churches and synagogues “came knocking” and asked how to help. These alliances were an experience of learning on the fly, responding to the needs of the moment of crisis as they arose.

Conclusion

In their interpretations of the story of Ibrahim  and Ismael

and Ismael  , scholars have noted the powerful example their relationship provides of different generations working together and learning from each other. Ibrahim

, scholars have noted the powerful example their relationship provides of different generations working together and learning from each other. Ibrahim  does not simply sacrifice Ismael

does not simply sacrifice Ismael  with no warning, but instead asks him “So tell me what you think,” recognizing in his son agency and offering his son the opportunity to obey the command of Allah

with no warning, but instead asks him “So tell me what you think,” recognizing in his son agency and offering his son the opportunity to obey the command of Allah  , an opportunity to show what he learned from the example of obedience that Ibrahim, Khalilullah

, an opportunity to show what he learned from the example of obedience that Ibrahim, Khalilullah  himself had set. Later, they would rebuild the Kaaba together, again showing the value of different generations striving for the sake of Allah

himself had set. Later, they would rebuild the Kaaba together, again showing the value of different generations striving for the sake of Allah  together. This must be our model as an ummah today: the young learning from those who came before them, different generations working alongside each other, men and women working alongside each other like Ibrahim, Ismael, and Hajar (may Allah’s

together. This must be our model as an ummah today: the young learning from those who came before them, different generations working alongside each other, men and women working alongside each other like Ibrahim, Ismael, and Hajar (may Allah’s  peace be upon them all) did, and all Muslims trusting one another to rise to the moment and obey the command of Allah

peace be upon them all) did, and all Muslims trusting one another to rise to the moment and obey the command of Allah  like Musa, Ibrahim, Ismael, and all His Prophets (may His Peace be upon them all) have done in the face of false ideologies and tyranny.

like Musa, Ibrahim, Ismael, and all His Prophets (may His Peace be upon them all) have done in the face of false ideologies and tyranny.

As they step into the leadership of a new movement for justice then, hopefully the new generation of Muslim-American activists can learn from the example of what the community achieved in bringing an end to the genocide in Bosnia. Today, like in the 1990s, the challenges may feel vast: from our positions as everyday people in local communities, people who have perhaps never been activists before this moment, it may seem impossible to organize a movement in response to a constantly developing crisis that can have an international impact. But Bosnia shows what is possible when, setting those anxieties aside, people step up, people answer the call to stand firm for justice, and claim a profound sense of agency. Bosnia shows that by the will of Allah  , more good will come when we take the first steps to do good, even if our inability to predict the outcome may fill us with dread. If activists today can do that, if we can honor the pioneering Muslims who came before us, then hopefully, those involved in ending the genocide in Bosnia can recognize us as their descendants in righteousness.

, more good will come when we take the first steps to do good, even if our inability to predict the outcome may fill us with dread. If activists today can do that, if we can honor the pioneering Muslims who came before us, then hopefully, those involved in ending the genocide in Bosnia can recognize us as their descendants in righteousness.

July 11th marked the anniversary of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, an act of genocide by Serbian forces that produced 8,000 Bosniak martyrs. In the words of Alija Izetbegovic, the first President of Bosnia and Herzegovina and a great Islamic thinker in his own right, “If we forget the genocide done to us, we are compelled to live it again. I shall never tell you to seek revenge, but never forget what has been done.” Today, we are called upon to honor and remember these martyrs by affirming over and over again the truth that they died for: La ilaha illallah muhammadur rasulullah. If we truly affirm that truth, we must stand against injustice and for Truth in every place, at every time. Let us honor our martyrs, from Bosnia to Gaza.

Related:

– Oped: The Treachery Of Spreading Bosnia Genocide Denial In The Muslim Community

– Srebrenica 2023: Political Instability And Rampant Genocide Denial