The Downfall Of A Tyrant: Bangladesh’s Sheikh Hasina Forced Into Flight After 15-Years Reign

The end, when it came, was swift. Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s latest, longest, and most lethal stint in power (2008-24) ended with an ignominious flight, after months of student-led protests that had lasted the summer against a violent crackdown. Having long milked, and abused, the legacy of her family and party in Bangladesh’s foundation, in the end, it was Hasina who was forced into flight after overplaying her hand.

In her latest tenure in power, Hasina had often exploited both her Awami League’s role in Bangladesh’s foundation and its secularist nature to crack down on dissidents. The latest trigger was a law that reserved quotas for the families of the “freedom fighters” of Bangladesh’s independence over fifty years ago; in essence this institutionalised economic privileges for a long-abusive Awami League that had already systematically and often viciously dismantled organized political opposition. Particularly to a younger generation that lacked their parents’ and grandparents’ emotive attachment to the Awami League’s role in independence and linked it to Hasina’s corrupt regime, the “liberators” of yesterday had become the tyrants of today.

A Long History Of Student Protest

Bangladesh has a long history of student protest that predates even the country’s foundation: students mobilised what was then called East Bengal against the British Raj, against discrimination and inequality in the subsequent era as East Pakistan, and even after Bangladeshi independence against successive predatory rulers. Hasina’s father Sheikh Mujibur-Rahman had himself led student protests against Pakistan, whose brutal crackdown in 1971 precipitated Bangladeshi independence. Assorted economic and linguistic injustices by a centralist Pakistani regime that tended to view Bengalis with disdain had led to a number of Bengali student protests. Opposition to Pakistani policies came from Bengali ethnonationalists – who varied from wanting the Bengali language institutionalized, to calling for a decentralization to calling for an irredentist union with the West Bengal of India – as well as from leftist, religious, and populist circles.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we’re at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small.

Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you’re supporting without thinking about it.

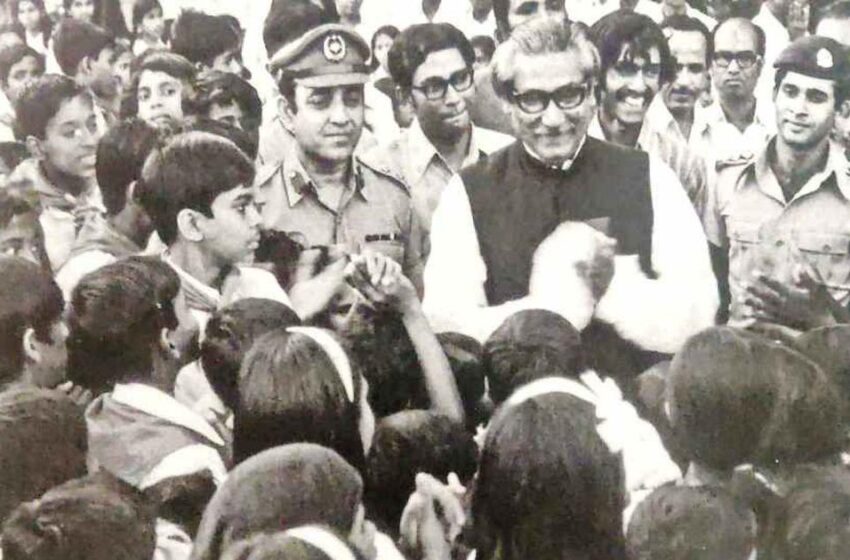

Children on the premises of the Ganabhaban on the occasion of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s birthday on March 17, 1975 [PC: Scroll.in]

Mujibur-Rahman had shot to fame through these protests, but no later than the late 1960s he had also secretly opened links with India at which many Bengali dissidents would have baulked. These links were partially facilitated by the minority Hindu business class, which has often been a strident supporter of the Awami League since. Nonetheless, his popularity forced the junta to permit him to run in the 1970s, and with virtually the entire East Pakistani electorate rallying behind him he won. This put the Pakistani junta, which had bet on a split Eastern vote, in a quandary: eventually, they arrested the election winner and savagely cracked down on much of the Bengali populace, students and Hindus in particular, in a campaign where thousands were killed. Large numbers of Bengali soldiers deserted to join a mounting insurgency. In late 1971 India seized the opportunity with a full-scale invasion to “liberate” Bangladesh, with Mujibur-Rahman as its leader.

Few Bangladeshis mourned the end of the dysfunctional marriage with Pakistan. However, Bengali Islamists, particularly the Jamaat party, who were otherwise critical of Islamabad had nonetheless refused to break up a Muslim country and had fought on the Pakistani army’s side in 1971. This made them ripe targets after independence, but they were not the only ones. Faced with the natural disasters that had also imperilled the late Pakistani period and with a large number of armed militias over which he had little control. The Bengali nationalism that he had ridden often manifested itself in ugly ways: as early as 1970-71 his Awami League’s armed wing had ethnically targeted non-Bengalis, who with the exception of the southeast hills were almost expelled outright from Bangladesh. He also faced the same natural disasters with which his Pakistani predecessors had suffered.

But perhaps most damaging was Mujibur-Rahman’s increasingly obvious vassalage to India, which outfitted and supplied a thuggish personal militia that his family used, supposedly to maintain control. This vassalage pleased neither Bangladeshis who wanted meaningful independence; nor irredentists, who wanted the unification of Bangladesh with India’s West Bengal province; nor Marxists, who tended to support India’s rival China; nor Islamists; nor the critical military defectors from the Pakistan army, who had fought against India just a few years earlier. Mujibur-Rahman’s progressively repressive regime ended in a brutal assassination that wiped out much of Hasina’s family. In the power struggle that followed, military factions led by army commander Lieutenant-General Ziaur-Rahman and his successor Hossain Ershad would take over.

Though military rule stabilised Bangladesh and generally lacked the brutality of Awami rule, a small elite continued to rule: Ziaur-Rahman’s Jatiyabadi Party and Ershad’s Jatiya Party are both led by their families to this day. When Hasina and Ziaur-Rahman’s widow Khaleda Zia rode a populist wave to end Ershad’s military rule in 1990, the succeeding democratic period continued to alternate rule among parties defined by patrimonial politics. Hasina, who returned to power in 2008 after a brief military rule had ousted the increasingly popular Khaleda, added brute force to this elitism.

A Venomous Elitism

The Awami League’s strident secularism, in the age of “the war on terror”, was particularly useful in beating down dissent. An early paramilitary mutiny was tendentiously blamed on Islamist infiltration and supposed Pakistan links – claims that were eagerly parrotted and repeated worldwide by Hasina’s Indian suzerains. She also proceeded to reverse her own father’s rehabilitation of the Islamist Jamaat, which was essentially vilified for having picked the Pakistani side during the 1971 war and banned, its elderly leadership executed as “war criminals” during a spree of show trials in the mid-2010s. Khaleda’s Jatiyabadi party, as Hasina’s main contender, was also persecuted. The worst episodes came during a series of massacres in the spring of 2013 when protests against these dubious sentences were bloodily crushed. Rather than focus on the actual bloodshed, much of the international media focused on the claims of government-friendly liberal bloggers who claimed intimidation by “radical Muslims”: this in an overwhelmingly Muslim country.

The now-ousted ex-PM of Bangladesh [PC: AFP/Getty Images]

It became fashionable at one point to highlight Bangladesh’s economic growth under Hasina. But this masked the reality that the state, particularly its security, had been outsourced as a barely concealed client of India, and that the economic and social benefits were reaped by a small and increasingly ruthless elite. Disappearances, abductions, and murders were frequent and rarely discussed. State institutions, including even an army that had historically had a sizeable number of opposition sympathisers, were purged in favour of the prime minister’s men: her last army commander, General Wakerul-Zaman, is a relative by marriage. Perhaps most notorious was the ruling party’s student wing, which was infamous for its brutality and impunity. Bangladesh’s political scene only narrowed, with Hasina’s election wins coming against either Jatiya members – Ershad’s widow Rowshan and brother Ghulam Qader – or by disgruntled Awami League leaders, such as former foreign minister Kamal Hossain. Whatever their respective merits and flaws, the process was hardly representative or participatory.

It was in an attempt to reward her supporters, by cementing quotas for the families of “freedom fighters” – in other words, for loyalists – that Hasina overstepped. The protests against this, led by Naheeb Islam, were quickly subjected to violent crackdown on her orders until it became clear that violence would no longer work. Hasina had misread the discontent of Bangladesh’s public, particularly its youth: appeals to the Awami role in the “freedom struggle” would no longer work. Having milked its role in 1971 for so long, the Awami League was utterly unaware that to a critical mass of the population, it had become the oppressor of the day.

What Now?

India, where she fittingly fled, has been most obviously dismayed by Hasina’s ouster, masking their loss of a pliant vassal with tendentious claims of threats to Bangladeshi Hindus – who themselves have largely dismissed these threats, and whom the opposition has vowed to safeguard. But its frequent rival China, which has always favoured stability even at the cost of repression, is not particularly enthused for its part. A surprisingly positive note came from India’s close ally the United States. Having long turned a blind eye to Awami misrule, Washington had been particularly concerned since Hasina cracked down on an opposition leader, Muhammad Yunus, who had a long track record of working with Washington and in particular the Clintons. Today Yunus sits as, effectively, prime minister of an interim regime.

The interim government, where Awami leader Mohammad Shahabuddin still maintains the titular presidency and Hasina’s relation Wakerul-Zaman leads the army, is by no means thrilled at the prime minister’s ouster. It may be, as in so many countries over the last decade, that the establishment will make a comeback. Or it may be that one particularly predatory party is exchanged for another, or another power finds a willing vassal at the expense of the Bangladeshi populace in Dhaka. Nonetheless, Bangladesh’s youth has done what years of repression had rendered unthinkable: caution need not be mutually exclusive with a justified celebration.

Related:

– Over Five Decades On: Bangladesh’s Crisis Of Islam, Politics, And Justice

– From Cairo To Dhaka: Exploring The Impact Of The Arab Spring On Bangladesh