From Algeria to Palestine: Commemorating Eighty Years Of Resistance And International Solidarity

Eighty years ago this month (November) marked the start of one of the most dramatic and bitter independence wars in the twentieth century: the liberation of Algeria from over a century of French colonization. In a period of decolonization where colonial European empires were beginning to recede from the world, the Algerian war marked an epochal shift, its anti-colonial insurgency and a brutal French counterinsurgency assuming ramifications that extended well beyond its own borders and gave succour to various liberation struggles around the world.

Background

Even in the colonial heyday of the nineteenth century, France’s colonization of Algeria had been especially notorious for its ruthlessness. The sprawling territory, yawning inland off its coastal metropolis of Algiers, easily outstripped France itself in size, and in fact was roughly the size of continental Europe. France thereby gained considerable prestige within Europe for this acquisition, fighting a series of local resistance leaders – most famously the gallant and resourceful Sufi commander Abdelkader. Over the decades the French empire launched a programme of mass settlement intended to displace the native Muslim Arabs and Amazigh, who were divided on ethnic grounds and rendered an underclass, with periodic suppression of their language and, to a lesser extent, faith. In the inter-World War period, Muslim elites fashioned contrasting responses to French nationalism: liberal politician Ferhat Abbas tried to increase Muslim representation within French politics to little avail; radical activist Ahmed Messali-Hadj rallied Muslim workers in the French mainland; and a group of revivalist scholars led by Abdelhamid Benbadis emphasised through education and activism the distinction of Islam in what became a rallying point of Algerian identity.

A French soldier uses a mine detector on passers-by on January 16, 1957, as part of a systematic search operation in the lower part of the Casbah, during the Battle of Algiers. (AFP)

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we’re at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small.

Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you’re supporting without thinking about it.

The pied-noirs, as French settlers were called, tended toward triumphalist rightwing versions of French nationalism. The fact that a large proportion had supported the “invigorating” Nazi conquest of France in the Second World War did not prevent the French government, after the war, from continuing to favour them. The tone was set as early as May 1945, when the colonial regime’s violent repression of Muslim demonstrations escalated to leave thousands of Algerians dead. More legalistic attempts at asserting Muslim rights across French-ruled North Africa also faltered: the 1948 election for the Algerian assembly was blatantly rigged, while in both Morocco and Tunisia – ruled by France in partnership with royal vassals – Paris ran roughshod over local opposition. In December 1952 Tunisian opposition leader Ferhat Hached was assassinated by far-right thugs linked to French security, and in 1953 Morocco’s popular sultan Mohammad VI bin Yusuf was exiled and replaced with a puppet.

Altogether this repression had already provoked antagonism against French colonialism in North Africa. Six months after a famous French defeat in Vietnam, the Front Liberation launched an insurgency with a series of attacks across Algeria. This shadowy group combined a number of Algerians from all walks of life including peasants, soldiers, workers, intellectuals, and activists: its most formidable early front was in the Aures mountains, where Moustafa Benboulaid led an active front, but it soon established a major presence in urban Algeria. The group had partly been frustrated into action by the ineffectiveness of the populist Messali-Hadj, who opposed it and set up a rival group that was soon infiltrated by France. By contrast, the liberal politician Abbas, formerly an opponent of independence, did join the Front, though he never exercised much influence. The Front was immediately backed by Revivalist Ulama leaders Toufik Madani and Bashir Brahimi, whose Islamic networks had taught a generation of Algerians and who provided an important ideological influence. By contrast the theoretically anti-imperialist French left split: French communists opposed armed revolt while the crackdown in Algeria was actually supervised by a series of left-leaning cabinets in Paris. Many frustrated activists would independently join the revolt, the most famous of them anticolonial ideologist Frantz Fanon.

The Algerian Forge

Though intermittent battles went on for nearly a year, in which Front founders Benboulaid and Abdelkader Didouche were killed, a turning point came at the end of summer 1955 when insurgent commanders Ahmed Zighoud and Lakhdar Bentobbal killed scores of piednoirs in a raid at Skikda. The French regime, regaling in the savagery of the slaughter, retaliated by massacring thousands of Algerians within a few days. Full-scale war erupted across Algeria and beyond: in Tunisia and Morocco, France was forced to relinquish its colonies after a series of fellagha or peasant uprisings, but it was determined to hold onto an Algeria that it considered an integral part of France.

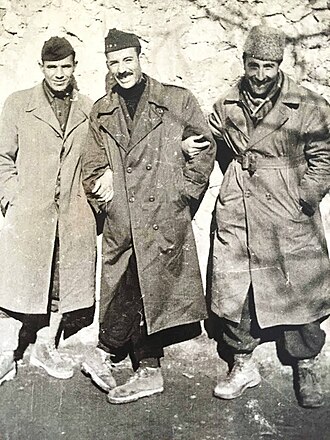

Colonel Amirouche Ait Hammouda (The Wolf of Akfadou Forest [centre] [PC: wikipedia]

Massacres and rampant torture abounded – epitomized in the 1956-57 Battle of Algiers, where another Front founder Larbi Benmhidi was captured and killed. Most of the remaining Front founders were abducted on a flight to Morocco. The most important remaining founder was Belkacem Kerim, from the Amazigh Kabylia region, a constant battleground through this period. Its commanders included Amirouche ait-Hamouda, a resourceful and ruthless veteran of many battles whom France nicknamed the “Wolf of Akfadou Forest”, and Nacer Mohammadi, a career soldier who flaunted a spiked Teutonic helmet to commemorate his days as an auxiliary with the German army. Other major leaders included Ramdane Abbane, who gave the Front its first formal organization, but was secretly killed in a dispute with Bentobbal, who led Front security. Friction between Front leaders intensified as in the late 1950s France cordoned off the border, cutting off supply lines, and attempted to infiltrate insurgent ranks: Amirouche became so paranoid over infiltration that he executed hundreds of students who had joined his ranks, while Nacer survived the first of several mutinies. At first, France tried to exploit such rifts by buying off insurgent commanders, but when one supposed defector – Algiers field commander Azzeddine Zerrari – turned out to be a double agent and instead defected back to the insurgency with valuable intelligence, they gave this up.

French propaganda played up their “civilizing” angle, castigating a massive Muslim-Arab conspiracy, claiming to emancipate Algerian women, and setting up a series of ceremonies where women were theatrically unveiled. Fanon caustically remarked on the cynicism of this ploy that the Muslim woman’s “veil frustrates the colonizer”. In fact, Algerian women were to play a key role in the insurgency, both in terms of reconnaissance, relief, espionage, and occasionally fighting. This was particularly important in the urban battlefield: Saadi Yacef, the insurgent commander in Algiers city, made liberal use of women informers, one of whom – Zohra Drif – would later marry Front founder Rabah Bitat.

France also emphasized the foreign links of the militants – in 1956 most of the Front’s remaining founders, including Ahmed Benbella, were abducted on a flight to Morocco. Cairo was particularly portrayed in European propaganda as the mastermind of the French revolt, and France joined Britain and Israel in launching an ill-conceived war over Suez, which ended in humiliating failure against opposition by the emerging Cold War powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. These giants, despite a formal criticism of imperialism, nonetheless abstained from supporting the Algerian insurgency: Moscow was preoccupied with its Eastern European vassals while Washington supported France.

Instead it was the “Global South” of decolonizing countries that provided the most strident support: virtually all Muslim countries, as well as China and India, backed the Algerian struggle. So too did various African independence movements: the strains of the Algerian war prompted France to slowly withdraw from other African possessions, the first of them Guinea in 1958. Nonetheless, the pressure of the piednoirs, who had major influence in security and military quarters, and France’s own self-image and prestige prevented it from withdrawing even as its brutality became notorious. For the same reason that Algeria was viewed as an integral part of France, events there profoundly influenced the French mainland in Europe in a way that other colonies did not. The large Muslim underclass in France came under particular scrutiny because of widespread sympathy for the revolt: in 1961 hundreds of Algerians in Paris were massacred.

A rally organized by the Algerian People’s Party in the early 1940s.

[Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Author unknown]

Even as Paris threw every resource into the war, the piednoirs and other rightwing Frenchmen complained that France had gone soft and urged an even harder crackdown, setting up paramilitary organizations often with the unofficial approval of the French military. Ironically, this “war party” in France invested its hopes at first in nationalist general Charles de-Gaulle, who took power following a series of political upheavals at the height of the war in May 1958. But de-Gaulle, who was as pragmatic as he was infamously egotistical, realized that France had no long-term future in Algeria and began trying to wield both carrot and stick.

Even as military operations intensified – thousands of Algerians, both civilians and militants such as the “Wolf of Akfadou” Amirouche, were slain in what Algerians call the “field of honour” – de-Gaulle reached out to Front leaders such as Kerim to offer negotiations. This provoked the ire of the rightwing that had originally backed de-Gaulle: in 1961, with the support of senior generals, they tried to mount a coup. This failed, and a year later de-Gaulle was able to sign with Kerim the Evian Accord, which stipulated a French withdrawal and the celebrated end of one of the most brutal colonial wars. In its aftermath, Algerians would chant, “Rejoice, Prophet Muhammad*! Algeria has returned to you.” It was no surprise that Algeria’s independence influenced a generation of anticolonial struggles, including the nascent resistance in Palestine.

*may Allah give him peace and blessings

The Algerian Shadow on Palestine

It is hard to miss the parallels between Algeria in the 1950s and Palestine today. As in Algeria, the supposedly civilizational supremacy of a “Western” power, Israel, in Palestine has provided thin cover for essentially far-right, supremacist settlement: the piednoirs in Algeria, the euphemistically named “settler” thugs of Israel today. Much as the 1955 Skikda attack was used to justify mass brutality, the 2023 breakout from Gaza has been exploited to justify enormous, recurring massacres of Palestinians. Much as France expanded its war from Algeria through northern Africa and up to Suez, so too has Israel expanded its war far beyond Palestine. Much as “Western” leaders and institutions – even those of a liberal or leftist bent – ended up siding with the French far-right in their suppression of Algeria, so too have today’s liberal institutions of various “Western” countries, from media to bureaucracy, thrown their weight behind the far-right Israeli regime and its genocidaires. Much as the Algerian crackdown fundamentally influenced French politics, so too has Palestine cast a long shadow on the domestic scenes of Israel’s backers, particularly the United States. The major difference is that while Muslim, and other anticolonial, leaders of the 1950s largely reflected their populations in backing the Algerian moudjahedine, such support has been critically lacking by today’s leaders in the Muslim world.

Related:

– Destroying Movements From Within: From Unveiling Algeria to Identity Politics

– Commemorating The Nakba: Profiles In Palestinian Resistance