The Seven Sleepers: A Story from Early Christianity Explained by Islam

© Shutterstock

Sarmad Naveed, Toronto, Canada

Christianity, as it exists today, is fundamentally predicated on the concept of Jesus’ (as) physical resurrection from the dead. Considered the prime miracle of Christianity, belief in the resurrection is a core tenet of Christianity and a matter of faith.

Centuries after Jesus (as), a story emerged in the Christian world and gained widespread popularity for a crucial reason; Christians believed it was another story of resurrection, affirming to them that resurrection was indeed possible and thus also true in the case of Jesus (as).

That story is of the Seven Sleepers.

It’s a story of seven Christian brothers who escaped religious persecution by hiding in a cave where they ultimately fell into a deep ‘slumber’, only to be awoken some 300 years later when persecution against Christians no longer existed.

It’s generally considered that this story was recorded in Greek literature, though the exact origins of its earliest versions remain unknown. It was in the late 5th century, leading into the 6th century, that this story gained renown through writings by the likes of Syrian bishop Jacob of Serugh, considered one of the foremost theologians in Syriac Christian tradition. Another famous rendition of the story, thought to be among the earliest preserved accounts was in Latin by Saint Gregory of Tours from the 6th century. He was a popular Gallo-Roman historian, known as the ‘father of French history.’ His credibility also extended to religiosity, as he was a bishop who wrote the accounts of early saints, including the story of the Seven Sleepers, recorded in his book De Gloria Martyrum (Glory of the Martyrs).

From then on, the story of the Seven Sleepers gained popularity throughout medieval times and beyond, including Western literature. It was popularised in Western Europe by Jacobus de Voragine through his seminal work The Golden Legend, a Latin book that detailed the stories of Jesus (as) , early saints, and miracles. It shaped modern understandings of medieval religion, art and culture. In fact, its English translation is considered to be among the first English books ever printed.[1]

The story of the Seven Sleepers is also mentioned by the famous Enlightenment-age British author and historian Edward Gibbon in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.[2] Even Mark Twain, regarded as the ‘father of American literature’, has referenced the story in The Innocents Abroad, published in 1869.

So, a story that gained widespread popularity and that Christians believe proves their fundamental concept of bodily resurrection is certainly worth exploring. But what exactly is the story?

According to one of the earliest known accounts by Saint Gregory of Tours, the story goes something like this:

It all started in a place called Ephesus – an ancient city on the west coast of modern-day Turkey – during the reign of the Roman Emperor Decius, who ruled from 249 CE to 251 CE. Being a polytheist himself, Decius’ empire was marked by grave cruelties and atrocities against Christians who faced imprisonment or the threat of losing their lives. In the course of these cruelties, seven Christian brothers were captured and given the option to either worship the many Roman gods or face execution.

The Emperor gave them time to think about their decision, but instead, the brothers seized the opportunity to flee and hide in a cave to escape the Emperor. They would assign one person at a time to go out into the market and bring back the necessary provisions for their survival, as they hid in the cave and prayed for God’s protection. They remained in the cave for several days, until one day a slumber overcame them. When the emperor learned of their whereabouts after an exhaustive search, he ordered, ‘Let those who refuse to sacrifice to our gods die there,’ and had the entrance to the cave sealed shut.

Many years later, the circumstances in Rome developed favourably for Christians, especially by the time of Theodosius II, who was a Christian and ruled as Roman Emperor from 408 CE to 450 CE. Though Christians were no longer being persecuted, there were still some people who denied the validity of Jesus’s (as) resurrection.

Gregory of Tours goes on to say that during this time, a shepherd ventured into the mountains looking for some rocks to build walls for his pens. He came across some rocks covering the mouth of a cave, which he took to serve his purpose; however, he did not see what was actually inside the cave. With the entrance of the cave uncovered, the Lord sent a breeze of life into the cave that awoke the sleeping men who thought they had only been asleep for a single night. And so, as was their routine, they sent someone to the market to bring back provisions.

When the assigned brother reached the market, he was astonished to find crosses publicly displayed, a bewildering sight in what he still thought was an anti-Christian climate. Still unaware that he had all but been transported into an entirely new time period, the brother presented a coin to pay for some provisions he wished to purchase. The shopkeeper was amazed to see the coin he paid with was from the time of Decius, thinking that this brother had uncovered some ancient hidden treasure.

The brother was taken to the bishop and town judge, who denounced him. Left with no other choice, the brother was compelled to divulge the secret of where he and his brothers had been hiding, taking the bishop to the cave so he could see for himself. The bishop witnessed that these brothers had indeed been hiding in this cave for centuries, as verified by a stone tablet in the cave that recorded their experience. Hearing this glorious and miraculous news, Theodosius II himself went to the cave and sat with the Seven Sleepers, who said,

‘A heresy has spread, glorious Augustus, that attempts to mislead the Christian people from the promises of God by saying that there is no resurrection of the dead. Therefore, because, as you know, we will all be held responsible before the tribunal of Christ in accordance with what the apostle Paul wrote, the Lord has ordered us to be awakened and to say these things to you. Take care lest you be seduced and excluded from the kingdom of God.’

After conveying their message, the men once again fell into another slumber and passed away.[3]

It’s a riveting account of bravery, courage, and faith. And while Christians believe this to have been a true event that serves as proof of the fundamental beliefs of their faith, not everyone is convinced that this version of events was a reality. For example, while mentioning the story, Edward Gibbon refers to it as a ‘fable’. For many, it requires a great deal of mental manoeuvring to accept that human beings could have slumbered for so long and awoken centuries later.

It begs the question: is this version of events a true story, or is there an alternate understanding?

The search for answers would be incomplete without recognising a crucial aspect: not only is this story found in the Christian tradition, but it is also immortalised in the Islamic scripture – the Holy Qur’an – in the form of a narration regarding the People of the Cave.

Chapter 18 of the Holy Qur’an – called Surah al-Kahf or the Chapter of the Cave – narrates that a group of youth who believed in One God lived in a society filled with paganism and polytheism. To escape religious persecution and preserve their monotheistic beliefs, they hid in a cave and prayed for God’s mercy and guidance. Hearing their entreaties, God kept them secluded in these caves, away from the torments of their society for some time; a society which associated partners with God. For them, it was prudent to protect their beliefs, so taking to the cave was the best course of action. Ultimately, those who sought refuge in a cave to protect their belief in One God were strengthened in faith by God, Who promised to grant them ease in their affairs.[4]

The reason the Islamic account is so vital to understanding this story is that it provides the parameters for discerning its reality. In the Holy Qur’an, God begins narrating the account of the People of the Cave by asking:

‘Dost thou think that the People of the Cave…were a wonder among Our Signs?’[5]

Here, God clarifies that although the People of the Cave were certainly a sign of God, they were not a wondrous exception to the laws of nature created by Him. In other words, the key to understanding the truth behind the Seven Sleepers or the People of the Cave lies in a narrative that does not involve their bodily resurrection.

So, what really happened?

Using the parameters set by the Holy Qur’an, an expert and unmatched commentator on the Holy Qur’an, Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad (ra), the Second Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, conducted an in-depth study to uncover the reality behind the People of the Cave.

His investigation begins by presenting an alternative narrative of the location, time, and manner in which these events occurred.

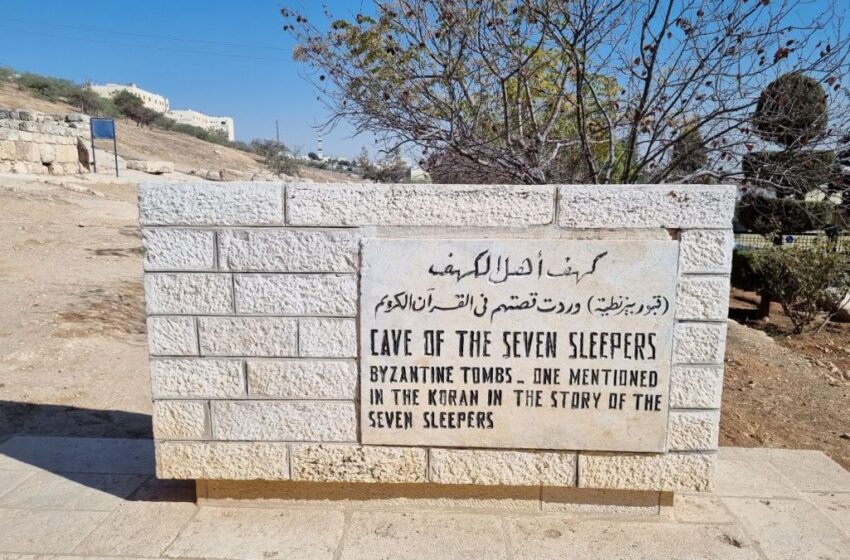

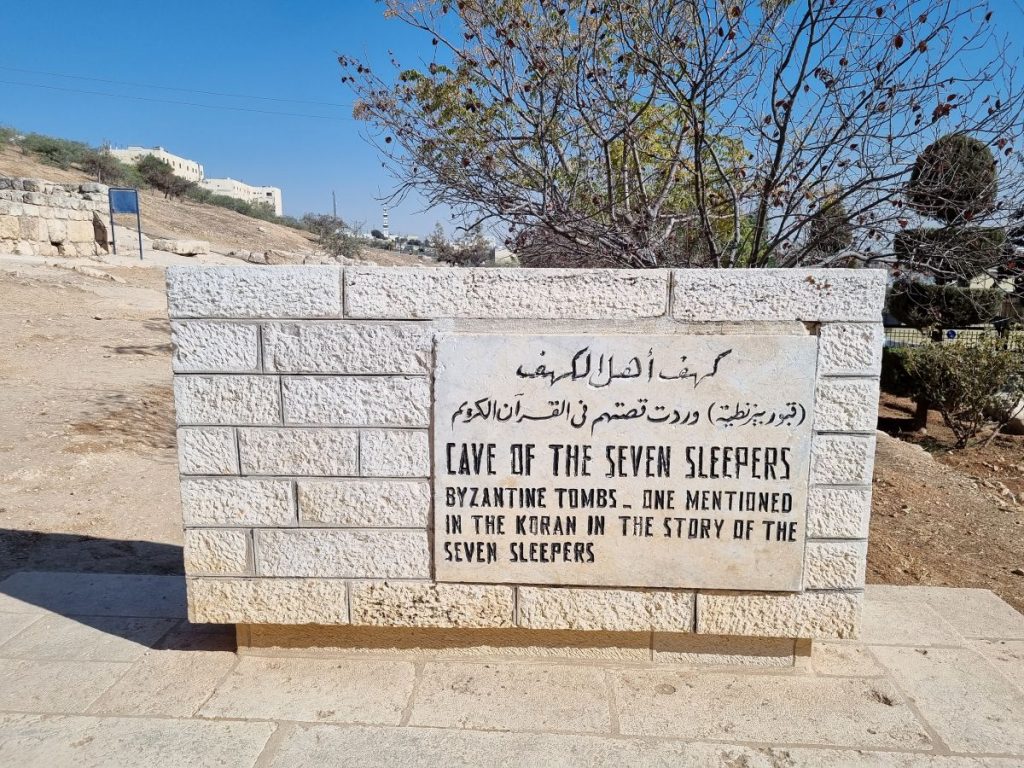

In traditional Christian accounts, the cave of the Seven Sleepers is placed in Ephesus, an ancient city on the west coast of modern-day Turkey. Others postulate that the cave was in fact in Jordan. However, Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s (ra) research led him to conclude that the cave where the People of the Cave took refuge is in Rome.

He came to this conclusion by examining the Catacombs of Rome. They weren’t your ordinary caves; the Catacombs of Rome were discovered to be three stories underground, equipped with passageways, schools, and even chapels – perfect for people wanting to remain hidden for an extended period.

These catacombs open a window into understanding the early history of Christianity in Rome and the persecution they faced. The connection begins with Saint Peter.

It’s commonly accepted that after his death, Saint Peter’s remains were moved to the catacombs located in Rome. What exactly was he doing in Rome in the first place? Well, Christianity was introduced in Rome primarily through Peter’s preaching efforts. In fact, Peter’s own presence in Rome during the first century is evidenced by the Letter to Romans by St Ignatius6, the third Bishop of Antioch, whose letters are often referred to for knowledge of the early Christian church.[7] This would have coincided with the rule of the Roman Emperor Nero, whose reign was from 54 CE to 68 CE.

Although Christians were always persecuted at an individual level since the time of Jesus (as), it was during Nero’s rule in Rome that their persecution became widespread. It was triggered by the great fire of Rome, a blaze that began in the cramped shops of the city’s urban area. The shops were made of wood and filled with flammable materials and crops, turning the blaze into an inferno that raged for over a week and caused mass destruction throughout Rome in its wake. People blamed Nero for the fire, thinking he had started it so he could rebuild Rome according to his personal liking. To deflect blame from himself while also bolstering his polytheistic views, Nero blamed the fire on Christians. This ultimately gave rise to Christians being seen as wicked and becoming widely persecuted.[8]

It was in lieu of this persecution that Saint Peter was also killed; hence, his remains were taken to the Catacombs of Rome during this period of mass cruelty against Christians. In this dire climate, the Christians needed to find a way to protect themselves, and indeed they did. Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad (ra) has quoted Benjamin Scott, former Chamberlain of London, who wrote about this early period of Christian persecution in Nero-led Rome in his book The Catacombs at Rome:

‘Even at that early period, the Christians, influenced by a regard for their safety, had commenced taking refuge from popular dislike, Jewish opposition, and the persecution of the Roman Government, in these subterranean fastnesses.’[9]

Indeed, these catacombs were the perfect place to preserve a people and their beliefs. Investigations have shown that the catacombs were not only caves, but they were also strategically excavated labyrinths with layers of security and opportunities for the Christians to hide if ever anyone came searching for them. They used retractable wooden ladders so that they couldn’t be followed into the caves, and each room had multiple entrances and exits. The entire labyrinth totalled a distance of approximately 870 miles. These catacombs were certainly primed for protection.[10]

Further attestation of the Christians taking to the catacombs in that early period is found in the art in the catacombs. In fact, the earliest Christian art dates back to those very drawings and depictions found on the walls and ceilings of the Catacombs of Rome from the 2nd century. Interestingly, they give us insight into the identity and beliefs of the people who were hiding in those caves. The drawings depict the early Christians as believing in One God, and regarding Jesus (as) not in a divine sense, but with esteem as a good shepherd.[11]

Hence, through the research of Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad (ra), guided by the Holy Qur’an, we learn that while early Christian accounts narrate these events from the time of Decius, it was actually during the time of Nero that Christian persecution began, and it was during his reign that Christians began seeking refuge in caves. It’s certainly true that while Christian persecution became widespread during Nero’s time, it became state-sanctioned during the time of Decius, taking the cruelties to new heights, as he ordered everyone to perform rituals and sacrifices for the Roman gods, and those who defied these orders would be imprisoned or killed.[12]

Far from a discrepancy, this actually sheds even more light on the reality of events and helps uncover the fact that the People of the Cave were not just a single group. In other words, there weren’t just ‘seven sleepers’, rather there would have been ‘many sleepers’ due to the widespread and longstanding persecution, as Benjamin Scott attests:

‘History identifies the Christians at Rome with the catacombs there. The persecutions were repeated again and again, under different emperors, during several centuries.’[13]

And so, the persecution which began during the time of Nero and reached new heights during the time of Decius continued into the reign of Galerius, who was the Roman Emperor from 305 CE to 311 CE. He maintained harsh treatment towards Christians, but towards the end of his life, became extremely ill. He thought this illness might have been the result of the way he treated Christians, so he lifted the laws sanctioning Christian persecution in 311 CE.[14]

In 324 CE, Constantine became the sole Emperor of Rome, marking the first time that the Roman Emperor was a Christian. As a result, the conditions of Christians in Rome changed considerably for the better, notably seeing their persecution becoming a thing of the past. This allowed Christians to live freely, out of hiding, and continue to flourish, especially during the later reign of the Roman Emperor Theodosius.

Now, having explored the historical context of early Christianity in Rome, and bearing in mind the Qur’anic principle when ascertaining the reality of the People of the Cave, the conclusion reached by Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad (ra) becomes unmistakable:

‘Having investigated these events, it becomes clear for us to understand that the People of the Cave were early Roman Christians who endured hundreds of years of persecution…We only find discrepancies because people thought that the account of the People of the Cave pertained to a single group of people. However, the reality is that this account is not limited to a certain group of people or moment in time; rather, it transpired with various groups of people in different eras.’[15]

The beauty of this historically evidenced conclusion is that it preserves and honours the legacy of those brave early Christians who stood firm in their monotheistic beliefs and were prepared to make the necessary sacrifices to boldly stand firm by their true faith, no matter what it took.

Thus, once again, the Qur’an shows how it is the perfect teaching, by also bringing to perfection the teachings of all previous religions, including Christianity.

Astonishingly, even without the explanation of resurrection, the People of the Cave have lived on to our times as well:

‘…I have also been given the title of “People of the Cave.”’

This declaration was made by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) of Qadian, India, who claimed to be the latter-day Messiah and the spiritual second coming of Jesus (as), elucidating that Jesus (as) was not bodily resurrected, nor would he return in the physical form; rather, his return was always intended to be in spiritual form. He explained that as the latter-day Promised Messiah, the similarity between him and the People of the Cave could not be more evident; just as the People of the Cave remained concealed for an extended period, so too was the advent of the Promised Messiah ‘hidden’ from the world for 1,300 years after the Holy Prophet Muhammad (sa).

The Promised Messiah’s (as) mission also closely resembled the efforts of the People of the Cave: preserving belief in the oneness of God at a time when people are straying from faith.

In his own words, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) states:

‘God desires to see a holy transformation in the people of the world. Just as any king naturally desires to see their majesty manifested, similarly, divine will intends to see the people of this world recognise the greatness and omnipotence of God, and for God – Who is becoming more and more hidden – to show a manifestation of His being to the world. It is for this reason that God has raised a man whom He has commissioned, so that the world may be cured of its leprosy, as it were.’[16]

It’s this very mission which the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community – followers of the ‘People of the Cave’ of the modern age in Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) – carries forth by preserving and conveying the message of God’s Oneness throughout the world.

What does this all mean for us today?

It’s a lesson that no matter how godless the world and society around us may become; no matter the forces and influences pulling people away from true belief in One God, we must adopt the spirit of the People of the Cave and ensure to preserve within us the true monotheistic beliefs, so that we may stand strong and spread the message of One God to the world.

About the Author: Sarmad Naveed is a missionary of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community who graduated from the Ahmadiyya Institute for Languages and Theology in Canada. He serves as Online Editor and is on the Editorial Board for The Review of Religions, and also coordinates the Facts from Fiction section. He has also appeared as a panellist and host of programmes on Muslim Television Ahmadiyya (MTA) International such as ‘Ahmadiyyat: Roots to Branches.’

ENDNOTES

1. “Jacobus De Voragine,” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jacobus-de-Voragine

2. https://www.ccel.org/g/gibbon/decline/volume1/chap33.htm

3. Gregory of Tours, Glory of the Martyrs, Translated by Raymond Van Dam, pp. 87-88.

4. The Holy Qur’an, 18:10-17.

5. The Holy Qur’an, 18:10.

6. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Peter-the-Apostle/Tradition-of-Peter-in-Rome

7. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Ignatius-of-Antioch

9. Benjamin Scott, The Contents and Teachings of the Catacombs at Rome (Longman’s Green and Co., 1873), p. 61.

10. Ibid, p. 485.

11. https://www.britannica.com/art/Early-Christian-art

12. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Decius

13. Benjamin Scott, The Contents and Teachings of the Catacombs at Rome (Longman’s Green and Co., 1873), 63.

14. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Galerius

15. Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad (ra), Tafsir-e-Kabir, Vol. 6, p. 483.

16. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as), Malfuzat – Vol. III (Islam International Publications Ltd. 2021), 169.