Between Japa And Sapa: Nigerians Unearth Ghosts Of Ramadan Past

Iya Alhaja e dide nile, nitori Oloun, saari ti too gbo!

Baba Alhaji e dide nile, nitori Oloun, nafila ti too ki!

The sound woke me up almost every day, long immeasurable minutes before my mum or Anti Sera, the maid, came to get us up for sahur. “Were”, sung by boys and young men in their early twenties, usually students in the local madrassahs, are irrevocably tied to my childhood memories of Ramadan. Going from street to street, singing with or without the accompaniment of drums, waking the neighborhood to prepare the sahur (for women) or pray supererogatory naafil (for the men) they were the communal wake-up call long before we all had handheld devices with inbuilt alarms. This art form would eventually devolve into Yoruba fuji music, but that is an entirely different subject.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we’re at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small.

Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you’re supporting without thinking about it.

At the time, my family lived in a three-bedroom flat in central Lagos. The compound had two or three buildings (we moved when I was nine, some details have fallen through the cracks of my memory) each with three levels, and three units on each level. With the norms of large family sizes and housing a myriad of distant relatives, there were probably over a hundred people living in that compound. A community unto itself, complete with a mosque just inside the gates, that high occupancy was most keenly noticeable in Ramadan.

From the increased attendance at salah, especially in the first half of the month, to the evening tafsir sessions held in the open expanse of the compound after ’asr every day. These culminated in communal iftar, a potluck-style event where people tried to outdo each other with the food and fruits they provided. We prayed maghrib in that air of fanfare, stomachs stuffed with local seasonal fruits (I was in my late teens the first time I saw a date), different assortments of paps, porridge, and foods we considered ‘snacks’ and placeholders – ogi, akara, moinmoin, tapioca, the list is endlessly varied. After maghrib, everyone retreated to their homes for proper foods, an array of carb-laden dishes that guaranteed half of us children were drowsy by halfway through ashamu (tarawih, in Yoruba.) Two minutes after we were carried or finally crawled into bed, the ‘were’ boys were at it again…

***

First year of boarding school, all of 11 years old, I was appalled to find out a lot of my Muslim classmates had never fasted before. The school also had no provisions for Ramadan. With a handful of other students, mostly older kids doing the actual work, we managed to extract a concession from the school for a modified meal timing. That was what we got: the standard school-issued breakfast at 4 am, and the cold dishes from lunch served alongside our dinner at 7 pm. Undeterred, we organized and encouraged, assigning different tasks to different students, talking the other kids into joining us. Six years later, when I was graduating, Ramadan was an unmissable event in that Muslim-(by a slight)-majority school.

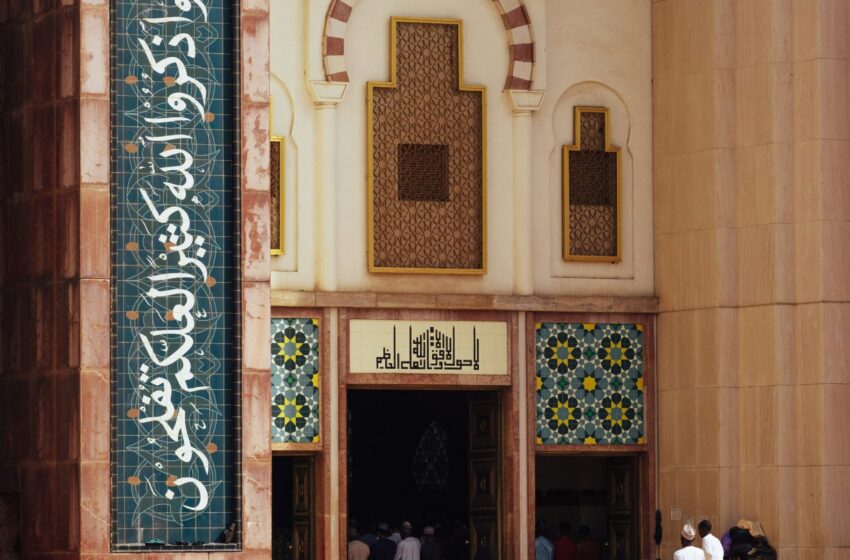

Mosque in Abuja [PC: Habila Mazawaje (unsplash)]

Sahur and iftar meals were prepared on a proper, special menu, taking into account the types and quantity of food fasting teenagers needed. Quality, unfortunately, was a feature we’d all learned to give up on within a few weeks of admission. We also began, for the period of the month, to pray in congregation: fajr (after sahur), isha’ and tarawih for which we were exempted from night prep. Initially led by the few male Muslim teachers, we later had a group of student imams, from the few who could recite the Qur’an. Held out in the open assembly ground, the festive air of tarawih – and the dressing accommodation: girls could turn up in colorful wrappers and hijabs over the ugly brown of the school-mandated ‘house-wear’ – resulted in a number of students suddenly discovering long-lost ancestors that were Muslim in their family tree. Everyone was welcome.

For my generation of Nigerian Muslims, university was when we connected spiritually with the deen. Ramadhaan was a particularly heady time, drunk as we were on what we were learning: of aqeedah, and fiqh, and stories of the Prophets and his companions, and Arabic, tajweed, the proper ways of doing our ‘ibaadah… For the first time in our lives, Ramadhaan was more than food and festive community, and we threw ourselves into milking every possible good we could from the month. We ‘raced for the goodness of our Lord.’ Organizing and attending circles of learning, we read the Qur’an and many, many beneficial Islamic books. We spent hours in tarawih, and even longer in our personal qiyaam-u-layl. And we prayed, making elaborate dua’ lists weeks before the month started, to ask for everything we wanted: from good grades and a good life, to brother Abdullaah bin Abdullah (or sister Umm Sulaym) as our chosen partner in both Dunya and Jannah.

***

As a mother of young children just beginning to build a medical career, the spiritual rituals of my university days are what stayed with me the most. I did not belong to any neighborhood Muslim community like my parents had back in the day: Nigeria had gradually moved into the culture of gated estates, in the face of rising insecurity. Besides, with an early career in medicine and 2 kids under the age of 5, it was all I could do to complete the recitation of the Qur’an once in Ramadan and pray the Salafi-approved 11 raka’ah of my qiyaam. Sahur, iftar, tilaawah, qiyaam: Ramadan became a me-and-my-children affair occasionally accompanied by decorations or a new picture book. This isolation, the loss of community, would be worsened – rather ironically – by our family moving to Saudi Arabia.

In the early 2010s, Saudi life was very segregated and women existed, for the most part, in the domestic realm. This did not change during Ramadan. Unless you were in Makkah, Madina, or another big city, the masaajid remained a male realm. It would take several years of finding myself in this new place, and a move to Madina, to find places open to women for tarawih. And that was the extent of it; even regular halaqaat of hifdh closed for the month. Unless you went to the Haramain, Ramadhaan in Saudia was pretty much a private/familial affair, especially isolating for a foreign female-led household. I yearned for the Nigerian Ramadhaan of my childhood.

Dates [PC: Saj Shafique (unsplash)]

When you move away, though, home moves on, too. The march of time is relentless, and time has not been kind to the Nigerian economy. For Nigerians living in Nigeria, the Ramadans I kept alive in my memories are a thing of the past. Many of them answered my call on Twitter, sharing their childhood memories of the month. Mayowa Oladeji, who was born of an interfaith marriage and accepted Islam as a teenager had this to say, “Lagos in the 90s, sweltering under the Harmattan’s dusty caress, hummed with a different rhythm during Ramadan. I, a curious eight-year-old, wasn’t a Muslim at the time, but Ramadan was an annual spectacle that painted my childhood memories in vibrant hues.”

“The pre-dawn call to prayer, a haunting melody echoing through the labyrinthine streets, would jolt me awake. I’d peek out the window, mesmerized by the silhouettes of neighbors scurrying towards the mosque, prayer mats clutched under their arms. The day stretched long, punctuated by the aroma of steaming moin-moin and golden akara wafting from nearby kitchens…

Come sunset, the world transformed. The muezzin’s call, this time a joyous song, ripped through the lazy twilight. Laughter crackled like electricity as neighbors emerged from their homes, faces aglow with anticipation. The air buzzed with an infectious excitement, a communal joy I yearned to share.

The mosque courtyard, usually quiet, became a vibrant tapestry of activity. Colorful prayer mats covered the ground, children chased each other in gleeful abandon, and elders sipped on dates, their faces etched with contentment. As the call to Maghrib prayer resonated, I’d stand mesmerized, watching rows of people bow in unison, their voices rising in a collective hum of gratitude.

The communal feast that followed was a sensory explosion. Platters heaped with jollof rice, spicy stews, and mountains of fried chicken were passed around, eliciting delighted gasps and satisfied sighs. Laughter mingled with the clinking of cutlery, creating a symphony of joy that resonated long after the last morsel was devoured.

As the days of Ramadan unfolded, I absorbed its spirit. I learned the value of patience, the power of community, and the sheer joy of giving. The dusty haze of Harmattan became a backdrop for a season of generosity, where the true feast wasn’t just for the stomach but for the soul. Even today, the Ramadan moon evokes a childhood memory painted in warmth, laughter, and the sweet taste of togetherness, a reminder that joy can bloom even in the harshest of environments.”

Unlike Mayowa, looking as he was from the outside, one of the most common threads of childhood Ramadhaan memories mentioned by the respondents raised Muslim include getting treats, as kids, for participating in Ramadhaan rituals: tins of milk after tarawih, gifts for the one who fasted the most among siblings, monetary gifts for every day fasted – varying from family to family, Nigerian Muslims from across different parts and ethnicities made the children included and invested in Ramadhaan.

The act of singing by madrassah boys to signify sahur time, called by different names in local languages, cut across geo-political zones. The communal tafsir / Islamic lecture sessions, after asr in some places, at night in others, was another recurrent memory. As is, by the overwhelming majority, the communal feel of iftar. Breaking the fast together as a community, potluck style so everyone brought what they could and no one went hungry appears to loom largest in the collective memory of Nigerian Muslims, home and in the diaspora.

***

Almost all of that is non-existent in the Nigerian Ramadhaan experience of today. The economic freefall and rising insecurity has driven the month more and more to an individual/family event, rather than a communal one. “People can no longer afford to feed other people,” Hawa says. “People no longer give gifts.” The Nigerians who can afford to, now exist behind locked doors and gates of their homes and estates; everyone is suspicious of everyone else.

The communal iftar of our collective childhood memories have devolved into a spate of food distribution campaigns with unoriginal names and slogans. We assuage our guilt by donating money to ‘charities’ that display no transparency. And they hand out meal packages to the most desperate members of our community, the only ones who engage with those ‘Feed a Fasting Person’ type drives. Everyone else “no longer trusts enough to eat food from other people,” Hawa concluded.

Within the confines of their homes, too, Nigerians are not smiling with the impact of the economy on their Ramadan. “The abundance of fruits for iftar has almost been erased,’ Saeedah says. Rafeeah agrees, “the food options and variety…It costs too much now…” Gone are the days of pounding yam for sahur almost every day, and iftar spreads every night. Nigerians back home have had to adjust to a leaner, lonelier version of the month, just like those of us in the diaspora.

And maybe there is space here for a conversation about moderation and the spirit of Ramadan, about focusing on spirituality and not food (or even community), about how full moon upon full moon would pass and there would be no cooking fire kindled in the house of Rasulullah. Or how many of our brothers and sisters in other parts of the world – Palestine, Sudan, Yemen – do not have the little we take for granted. Yet for many Nigerians the nostalgia for the Ramadan of old lingers, even as we tighten our metaphorical girdles for the ones to come.

May Allah  make us from those who benefit from Ramadan.

make us from those who benefit from Ramadan.

Related:

– Islam In Nigeria [Part I]: A History

– ‘Religious’ Violence in Nigeria fueled by Poverty and Ethnicity?